Just a fair forewarning: This post may sound a bit preachy, so please forgive me in advance. I do not truly believe that people are morally bankrupt for not considering what I’m about to lay out here, rather, this is just intended to expose some cognitive blindness we all have.

We all know how important it is to frequently express gratitude for all of the blessings we enjoy in our modern lives. As some of the luckiest people to ever be born, the best way to slow down the hedonic treadmill and regain a sense of perspective is to remind ourselves of how fortunate we are. It’s hard to get upset about a $125 speeding ticket when we remember that we will still eat tonight, we still have the same wonderful opportunities ahead of us, and we will likely not even remember the annoyance in six months’ time.

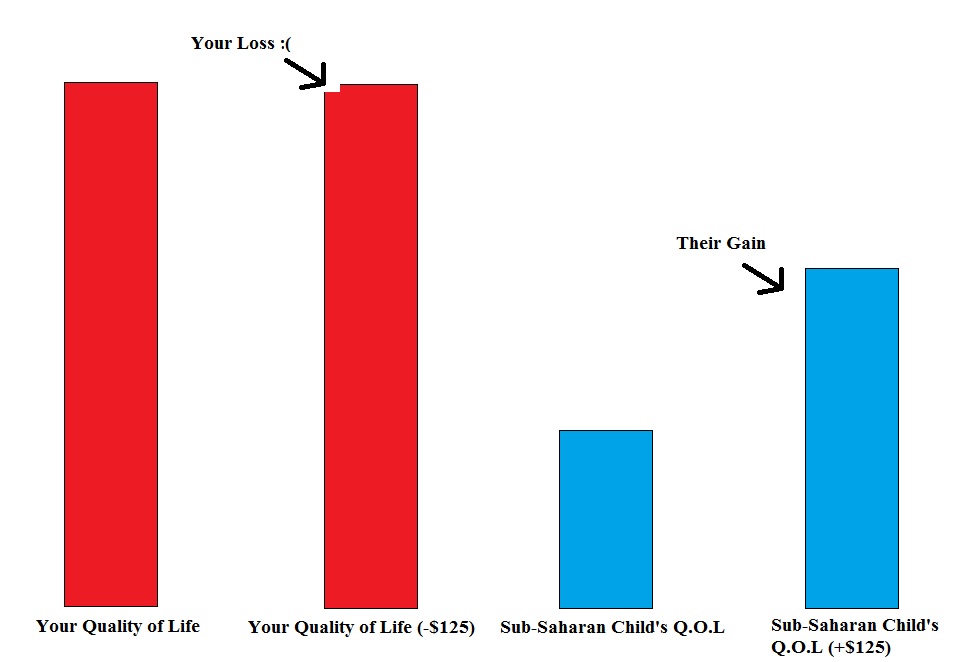

And yet. Despite this knowledge, we often turn a blind eye to the fact that the same amount of money (or a little bit more, but not much more) could be absolutely life-changing for a person in real need. Let me repeat again, with an illustration. The tiny inconvenience of losing $125 for us might reduce our quality of life by a total of 0.001% (as in, we’ll still eat, we’ll still have a roof over our heads, we’ll still have a job, we’ll still still have all of the same major necessities and luxuries that make our lives so wonderful). That same amount of money, for a family in Sudan, might be the difference between life and death. It might be seed grain for a farmer who lost his crops to blight. It might be an anti-mosquito net to protect a child from malaria. It might be a microloan to a would-be businesswoman in Sub-Saharan Africa. Suffice it to say, that money could be life-changing.

(And the picture doesn’t even consider the jolt of endorphins you get from donating to a good cause, but that’s for another time.)

Let me paraphrase one gut-wrenching parable for you all before we talk about a specific plan of action.

I want you to imagine you’re walking down the street in your brand-new $3000 suit. You are ready to crush your first day as a Wall Street executive, and as you walk to your car in front of your apartment, you hear a scream from above. Just two floors above you, a woman, covered in blood, is holding a crying baby, also covered in blood, out the window. With a wordless scream, she drops the baby down, directly towards you, standing below. You would ruin your fresh new suit if you caught this bloody baby. But if you step aside, the infant will almost certainly hit his head on the pavement and die. The question is: do you save the baby?

Dark, I know. But in effect, it asks a simple question. How much do you value the life of a stranger? If you would save the baby (and I hope most of you would) then why would you not forgo the expensive suit in the first place, and spend the difference on life-saving charity? Or, if you feel that you must have an expensive suit to look professional in the office (although I am sure that a $1000 suit would suffice), why do you need a BMW when a Toyota would serve the same purpose, while saving upwards of ten children’s lives?

I understand that it is easy to ignore the suffering of those we cannot see. Believe me, I get it. I also recognize that there is economic value in spending money on material goods within your own locality. By spending locally, you may be creating or improving jobs right here at home. But too often, we build up large material wishes in our heads, “American Dream”s flush with houses, cars, vacations, private education for the children, retirement, and more. I merely suggest that every so often, in addition to expressing gratitude for what we have, we also stop and take a look at the hidden opportunity costs that come with our preoccupation with material excess.

Postscript: Counterpoint and resources to help you take action:

Robert Reich, former Labor Secretary under Bill Clinton, sparks an interesting debate here about the actual value of philanthropy, specifically within philanthropic foundations, which avoid taxes and serve the wishes of a small board of directors. This is not to say that philanthropic spending is worthless, rather that we should be careful in considering the best way to channel that spending.

Apropos of that, two websites that I found interesting in my desire to learn more about effective altruism were www.givewell.org and www.80000hours.org.

And as always, I love to hear your thoughts and feedback.

Hmm, interesting to stumble upon this. Really glad you are sharing this on facebook.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/05/opinion/sunday/nicholas-kristof-the-trader-who-donates-half-his-pay.html

Maybe you’ve already read about him, but I thought I’d share in case you or readers haven’t. Matt Wage was a recent Princeton grad who decided to go to Wall Street instead of become a Philosophy professor so that he could make more money and donate it, and therefore do “more good” than he would have as a professor.

I had read the article once, kind of forgotten about it, but it’s a really interesting object lesson in pragmatic altruism. Thanks for the heads up!

You end up with a problem once you start applying ‘opportunity costs’ to charities: Some lives can be saved with $150 and some can only be saved with $15,000. You should be morally obligated to donate only to the charity that saves the most lives per dollar. It becomes ‘wrong’ to donate to a charity for terminal patients who can’t pay for a lifesaving surgery, or even any charity that doesn’t actually save people’s lives. After all, how can you possibly justify saving 1 life at the cost of saving 100 others?

Hey Jay, thanks for the comment. I think you are correct in theory. In practice, this brushes up against the issue of “Perfect is the enemy of the good” in the real world. If a person wants to give, we should always commend them for that. If they want to give to a foundation that we believe is ineffective, we can gently let them know that there are better charity options out there. Bob’s article recommendation is particularly appropriate here, as the author concludes that there is still value in supporting less lifesaving causes, like the symphony orchestra. The solution for a person who is mentally prepared to let data do the talking regarding where he should put his charity dollar is to use a resource like http://www.givewell.com and donate to the charities listed there.

Basically, I’ll give directly to poor homeless people begging outside when I see them (impulse giving) and once I have a bit of money from working, I’ll be making a donation to the Against Malaria Foundation or GiveDirectly (data-driven giving). I don’t tell people that they are wrong to give to other organizations, unless I think that they are prepared to handle that sort of moral criticism.

Incidentally, what do you think about the value of giving to support scientific research or space exploration? If we give money to fund research that cures AIDS, that’s worth so much in terms of lives saved. Maybe the expected value of that donation is also something to consider. Just food for thought.

Hope this clears up my opinion!

Ben

This is why modern economics and globalization fucks with out heads. Humans cannot keep track of all the people in the world, or at least genuinely care about them. I could be wrong, selling to scientific authority and Dunbars number, but still.

The world would be way better off if 50% of the individuals in the population were philanthropists helping the other 50%.

What I mean by that is that each person would see the fruits of their efforts directly, building more meaningful relationships with people, and those on the receiving end would perhaps gain a sense that people instead of institutions actually care about them. This would hopefully reduce a sense of learned helplessness of the homeless and impovereshed, excluding the severely mentally ill like schizophrenics and psychotic.

The world will change when we stop talking about this stuff so much in public policy meetings and board rooms and just get individuals to take care of other individuals on a case by case basis. You would see homelessness next to nil, poverty slashed, and hunger vanish overnight. We have the resources and wealth. We lack the courage and intellectual vision. The fear and power based culture we have will need to collapse in favor of an anarchist system based on individuals being loving and kind to one another.

End rant lol

Idealistic, but true. Again, the perfect is the enemy of the good. I think you’re discounting a lot of the unsavory elements of human nature that would prevent this system you posit from ever being realized. Collective planning and long-term vision needs everyone to buy in, and that is just not going to happen with so many powerful interests who emphatically do not want that.

I’m sure you’ve already read this Atlantic article, but still a worthwhile look at the pitfalls of so-called altruism and the people trying to make headway there. Peter Singer has probably been the most controversial professor at Princeton in recent years (rivaling Cornel West, who is controversial for totally different reasons), and it’s simply because comparing our marginal losses to the much larger gains of others simultaneously gives wealthy people guilt and hardens their hearts. Overall, it’s an idea we should constantly be toying with in our heads.

Mike,

Yep, that article was great, and it brought effective altruism back to the forefront of my mind, especially when I read it just as I was starting my new job.

You’re right, there are a ton of issues with preaching “altruism, altruism, altruism!” all the time, not least of which is that guilt is, as you said, not the best motivator. I’m not 100% sure that I understand why it hardens their hearts, although I suppose that it’s the same reason why motherly nagging can often have the opposite of the desired effect, building resentment. I think that the well-adjusted individual can, and should, frequently examine how they can be most effective (hint: donating to superPACs is probably the wrong way to go!) but I do try to remember that not everyone can be Mother Teresa. The best way to start, of course, is with self-reflection. Keep your own heart from hardening with regard to the lavish lifestyles of the wealthy, and you’ll have a much easier time convincing rich folks to give some of their wealth to those in need.