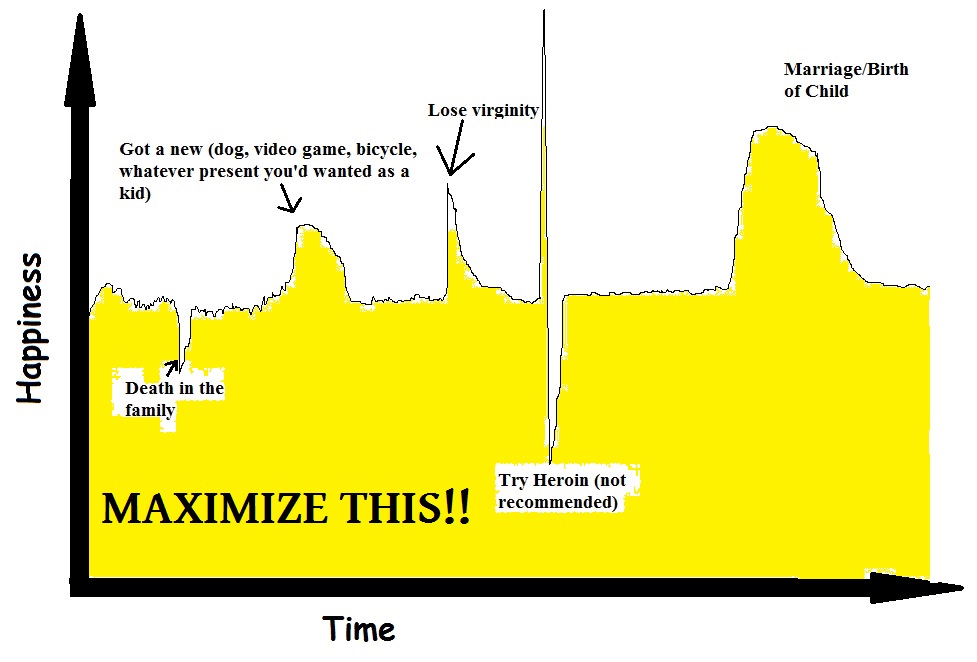

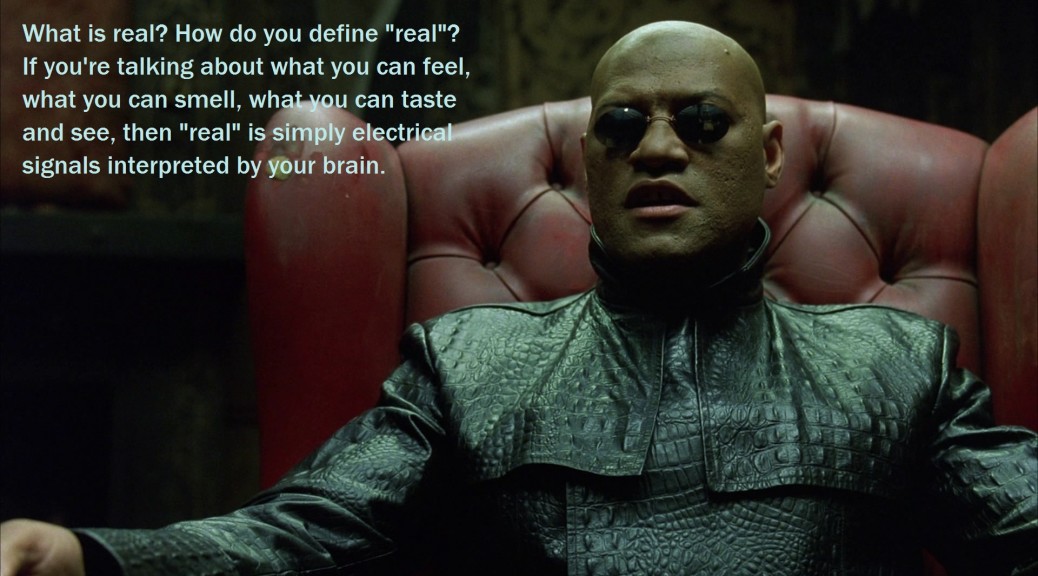

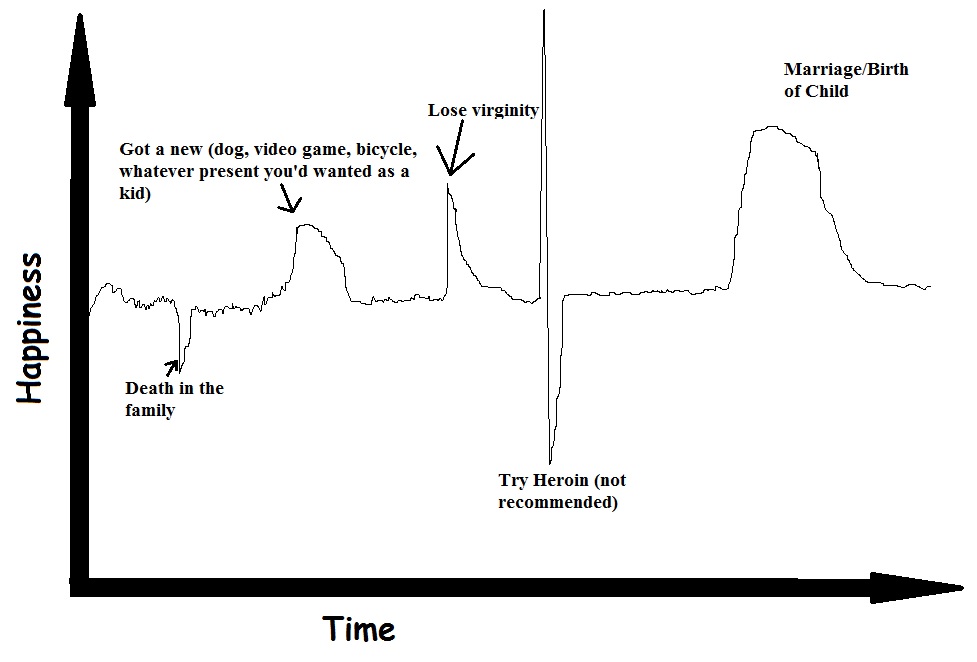

When we last left off, we had built up from a singular postulate, “I think, therefore I am”, to the philosophy of Solipsism. A natural progression, then, took us from the idea that the world might as well be a giant virtual reality game playing solely for us, to the conclusion that the ultimate goal in life was to maximize our happiness. Indeed, to quantify that goal, we can visualize our happiness as a graph charted over time, where our objective is to maximize the integral of happiness over time. To make it more palatable, I called a well-designed pursuit of that goal Conscious Hedonism.

It’s so simple! Just do more of the things that make you feel good. After all, it’s all about you. You don’t know that anyone else really exists, and when you die, it all disappears, so combine nihilist and selfish tendencies, add a healthy dash of cold logic, and voila! Instant recipe for happiness.

Well, to be honest, this is an excellent paradigm for finding happiness…temporarily. The flaw in the plan appears bit by bit, and for some people it takes many years to realize why this model for happiness is flawed. We often find those people lamenting the demise of their “glory days”, wondering where to go now that the thrills of the fast life have left them in the dust. What gives? They often pursued short-term pleasure with a dogged persistence, and now they regret those decisions?

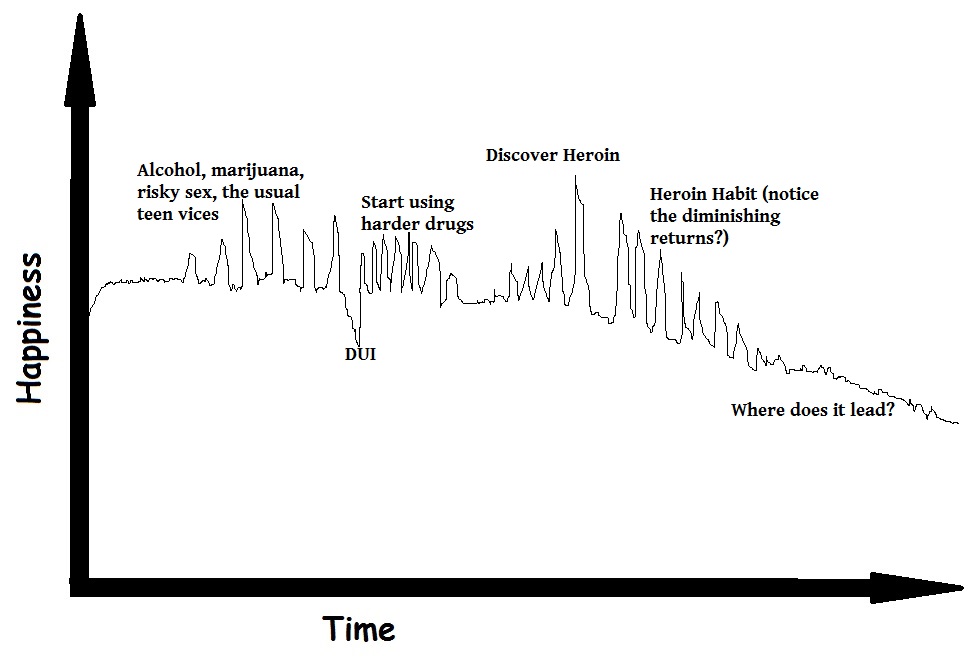

Quite simply, empathy pays dividends, happiness-wise. Consider an extreme case. A man who actually, deep in his heart, believes that no one else is important. Chalk it up to a wholehearted belief in solipsism, but he cannot bring himself to feel sorry for a beggar, or a cancer patient, or an abused child. To him, it’s all just a part of the big video game of life, and he chooses to turn a blind eye to those problems in order to focus on himself. Sex, drugs, gambling, fast cars, all the traditional vices are the pillars of his life. But cocaine begets a dependency, and gambling runs him into debt, and his lovers abandon him when he never reciprocates emotionally. Quicker than he’d anticipated, the roller coaster ride that was his exciting life starts sliding downhill. With no one left who cares about him, a lifetime of prioritizing short-term pleasure over long-term fulfillment exacts its painful and lonely toll. So, do you think he ends up regretting his choices?

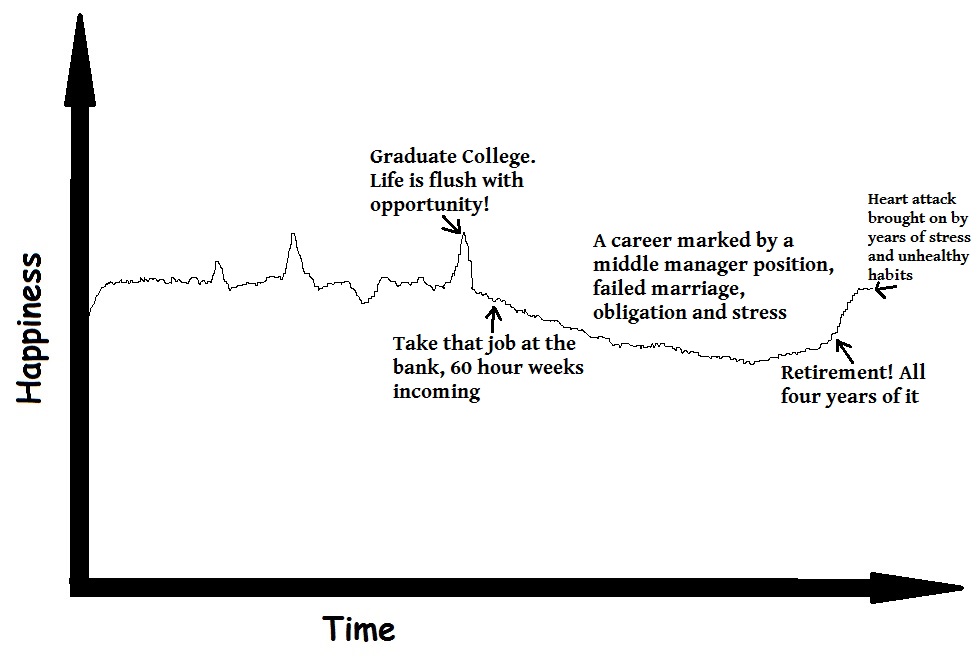

Or consider a different sort of selfishness. Consider the workaholic, passionless banker. He works 80 hour weeks to win the ephemeral rat race, making millions, which he has to use to patch the holes in his marriage and his relationships with his children. There’s no love in his life, because he has become an emotionless robot, with no cause to fight for and no ability to enjoy his life. He trades his time for money, and he doesn’t even derive meaning or satisfaction from his job. By putting off relationships and the search for meaning, he delays gratification until he has one foot already in the grave. He, too, fails to practice empathy. Don’t believe me? He exists. And not just John, but in every city on the planet, people have capped their happiness by denying their own humanity (read: their sense of empathy).

Now, let’s change that graph again, to show what it looks like when you either front-load gratification or delay it for too long.

Here’s what happens if you neglect relationships in favor of working more.

And here’s what happens if you can’t escape the trap of instant gratification.

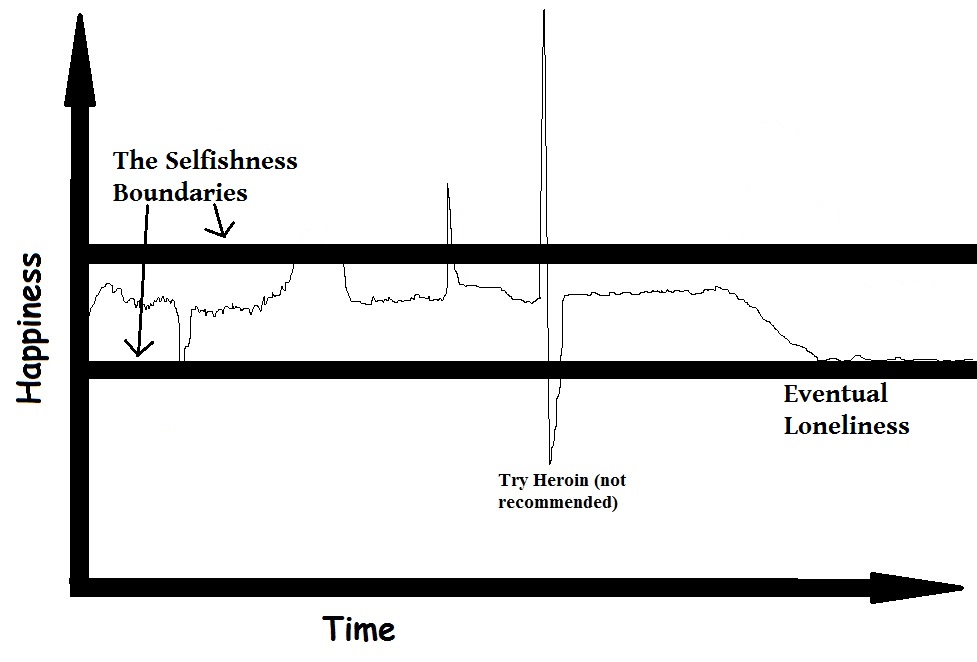

But of course, no one’s arguing with the devastating effects of either one of these lifestyles, and the conscious hedonist would argue that he or she would never follow such an unbalanced path. Of course, these self-destructive lifestyles are anathema to a conscious hedonist, but why must we move beyond hedonism altogether? To put it another way, we’re trying to find a logical reason to move forward from the paradigm of “me me me” and towards recognition of others as equally, if not more, important than us. Essentially, we want to dismiss Solipsism as a useless philosophy for purposes of maximizing our happiness.

Why should we do this? Well, the simple fact is that longer-lasting happiness and fulfillment with life demands that we exercise empathy, the act of considering the perspective of another when making our decisions. What is the highest form of empathy? I would posit that it coincides with the highest form of happiness. Love. Love is what Solipsism misses entirely, because how can one love another without acknowledging their reality?

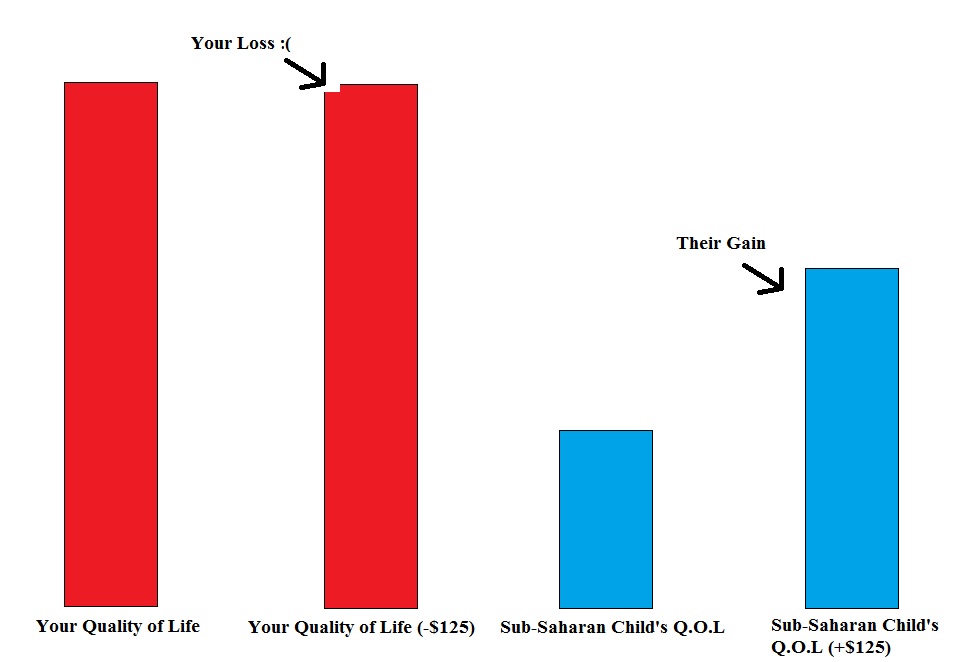

To return to our graphical analogy, Solipsism puts strong caps on the amount of natural, long-lasting happiness we can obtain. You will never rise above a certain level of happiness for long without accepting your fellow humans as being as real as you. There is a biological basis for that assertion, in what are called mirror neurons. Some scientists claim that mirror neurons form the physiological framework for empathy, and denying that basic biological inclination for empathy would be ill-advised. From the simple fact that humans are social animals, and wired to empathize, to the fact that we often feel significantly better after helping those less fortunate than us, there is no escaping the need for empathy as a key ingredient for happiness.

The stiff upper bound on happiness (at least, happiness that lasts longer than a few minutes) all but demands that we discard Solipsism and accept as a second postulate in our growing philosophy that other humans exist, they are valuable and worthy of our empathy, and that helping others is often more rewarding than helping ourselves. But don’t just take my word for it. This excellent article digs deeper into the need to give back and work towards a larger societal goal as a prerequisite for true satisfaction in life.

And isn’t that a little odd? By starting with Solipsism as the least assumptive philosophy after accepting “I think, therefore I am” as our first postulate, we quickly find ourselves rejecting the philosophy entirely from a utilitarian point of view. If Solipsism tells us to focus on making ourselves happy, then we must immediately throw it out for the simple fact that Solipsism is a happiness dead-end.

What’s the next step after accepting the existence of a world outside ourselves, along with all its inhabitants? Well, I’d guess that working on a large-scale quest to better humanity is a pretty good place to start. Just because reality may not exist solely in your head, doesn’t mean that you can’t work hard and possibly reshape the world. After all, you’ve got nothing if not a life full of opportunity in front of you.